Introduction

The purpose of this report is to provide a brief introduction to the civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS) system in Peru. The information was based on a case study of Peru’s CRVS and identity management system, published in the Compendium of Good Practices in Linking Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) and Identity Management Systems, and supplemented by a desk review of available documents. Among other things, the report presents:

- Background information on the country;

- Selected indicators relevant to CRVS improvement;

- Stakeholders’ activities; and

- Resources available and needed to strengthen CRVS systems.

Disclaimer: The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Country profile

The Republic of Peru is located in the Andean region of South America. It borders Ecuador and Colombia to the north, Brazil to the east, Bolivia to the southeast, Chile to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west.

Peru’s territory is divided into 26 units — 25 regions and the Lima Province. The regions are subdivided into provinces, which are composed of districts. There are 196 provinces and 1,869 districts in Peru.

1,285,000

31,989,256

1.7

22%

CRVS Dimensions

Birth

| Completeness of birth registration |

98% (2016 |

| Children under 5 whose births were registered |

96.7% (2014 |

| Births attended by skilled health professionals |

92% (2016 |

| Women aged 15-49 who received antenatal care from a skilled provider |

95.6% (2015 |

| DPT1 immunization coverage among 1-year-olds |

90% (2018 |

| Crude birth rate (per 1,000 population) |

18 (2018 |

| Total fertility rate (live births per woman) |

2.3 (2017 |

| Adolescent fertility rate (per 1,000 girls aged 15-19 years) |

57 (2017 |

| Population under age 15 |

29% (2012 |

Death

| Completeness of death registration |

69% (2011 |

| Crude death rate (per 1,000 population) |

5 (2017 |

| Infant mortality rate (probability of dying by age 1 per 1,000 live births) |

11.1 (2018 |

| Under five mortality rate (probability of dying by age 5 per 1,000 live births) |

13.3 (2019 |

| Maternal mortality ratio (per 100,000 live births) |

88 (2017 |

Marriages and divorces

| Marriage registration rate |

Not available |

| Women aged 20-24 first married or in union before age 15 |

3 (2017 |

| Women aged 20-24 first married or in union before age 18 |

22 (2017 |

| Divorce registration rate |

Not available |

Vital statistics including causes of death data

| Compilation and dissemination of CR-based statistics |

Available (N/A) |

| Medically certified causes of death data |

Available (N/A) |

Civil registration system

Legislative Framework

When Peru’s Registro Nacional de Identificación y Estado Civil (RENIEC), or national registry of identity and civil status, was created in 1993, the responsibilities for civil registration and identification fell under a single national agency. However, RENIEC was only officially established in 1995, with the enactment of Peru’s Organic Law. Other relevant laws that relate to RENIEC’s work are:

- Digital Signatures and Certificates Law (2000);

- Law that Regulates the Reconstruction of Birth, Marriage, and Death Records due to Negligence, Accidents, or Criminal Activity (2009);

- Personal Data Protection Law (2011); and

- Digital Government and Digital Identity Law (2018).

Management, organization and operations

RENIEC was created as an autonomous agency with constitutional independence, which is considered by most of its members to be the cornerstone of its stability and sustainability. RENIEC’s National Director is elected and can only be removed by the National Board of Justice. As established in the Constitution of 1993 (Art. 176), RENIEC is the only agency with the constitutional mandate to provide civil registration services, issue national identification documents, and manage the unique identification register.

RENIEC has exclusive authority over identification functions, but in some cases the agency has delegated the responsibility for civil registration to the Offices of the Registries of the Civil State (OREC). These offices were once part of the decentralized network of civil registration offices that existed before RENIEC. They have not been fully incorporated into RENIEC, but they provide civil registration services. There are more than 1,300 decentralized civil registration offices under municipal governments, which represent 21 percent of the total number of offices but reach more than two-thirds of the population.

National CRVS systems coordination mechanisms

Information not available.

Administrative level registration centres

In total, RENIEC provides services at more than 4,800 offices, either directly or in cooperation with municipal governments (Table 1).

In 1996, RENIEC delegated part of this responsibility to municipal governments, since the integration of thousands of offices was not possible in the short term. However, RENIEC has been implementing an integration strategy to gradually absorb all offices into its structure (Table 2).

In addition to more than 6,000 offices, there are 204 consular offices that provide civil registration and/or civil identification services. To speed up delivery of documents, RENIEC uses courier services for weekly deliveries to and from 89 of its consular offices.

Accessibility of civil registration services

No precise data available.

Registration of vital events

Timely birth registration must be done within 60 days after birth, or within 90 days in remote or border areas and Indigenous and rural communities. Births that occurred in health facilities where there is an auxiliary civil registration office are expected to be registered within three days. The person declaring the birth must present a certificate of live birth issued by a health facility, their national ID card, and a certificate of marriage in the case of children of married couples. If they are registering the birth late, they may provide additional proofs of birth, such as

- certificate of baptism;

- proof of school enrolment (noting the last grade the child attended); and

- declaration of two witnesses (who must be adults and present their national ID card).

There is no legally defined deadline for death registration. In order to register a death, an individual must present their national ID card and a certificate of death signed by a health professional or, when no health professional is available to certify the death, a sworn statement by a political, judicial, or religious authority. The deceased’s national ID should be returned or the declarant must present a sworn statement that the card is lost.

Marriages concluded in municipal offices that perform civil registration are automatically registered by municipal officials. When marriage is concluded in municipal offices without a civil registration function, these offices must send notification of concluded marriages every 15 days to the closest civil registration office. To register a marriage, one or both spouses must request the registration and present a national ID card.

According to the Constitution (Article 52), all individuals born in Peruvian territory (jus soli) and those born abroad to a mother or father who is Peruvian by birth (jus sanguinis) have the right to Peruvian nationality. Jus soli is applied regardless of the parents’ migratory situation. If a birth occurs in Peru and applicants bring proof of birth (certificate of live birth or sworn statement by a community authority), the newborn will be registered as Peruvian. To register the child’s birth, a foreign applicant can present their migration card, passport, or the national ID from their country of origin.

Vital statistics system

The National Institute of Statistics and Informatics is an agency responsible for regulating, planning, directing, and coordinating statistical and informatics activities. Its functions include

- producing vital statistics derived from the civil registry, which records vital events; and

- approving the statistical forms for birth and death certification in coordination with related organizations.

In 2016, the National Institute of Statistics published its report, Fertility, Mortality, and Nuptiality in Peru, using information provided by RENIEC. It still relies on a variety of sources to produce vital statistics on births and deaths (e.g. RENIEC, Ministry of Health, sample surveys, census), but information on marriages is drawn exclusively from civil registration data. According to the National Institute of Statistics, information on births, deaths, and marriages is crucial to

- studying population growth;

- implementing public health programs for reproductive, maternal, and child health; and

- planning and implementing housing policies and child protection programs.

National Institute of Statistics and Informatics). 2016. Fecundidad, Mortalidad y Nupcialidad, 2015. Lima, Peru. inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1407/libro.pdf

Causes of death

Cause-of-death information is communicated to the National Institute of Statistics by RENIEC, but the Institute also uses the information supplied by the Ministry of Health for statistics production (Table 3; Figure 1).

(Figure 1)

In 2015, in agreement with the Ministry of Health and the National Institute of Statistics, RENIEC developed the Sistema Informático Nacional de Defunciones (national computerized death certification system). That year, only 56 percent of deaths had a medical death certificate and around 30 percent of causes of death were considered ill‑defined.

- allows for online death certification;

- decreases the time required to issue printed death certificates; and

- creates a single, current national database of deaths.

Medical personnel can search and select the ICD-10 (World Health Organization’s Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) code to assess the cause of death. They can also access the deceased person’s and medical professional’s ID information from RENIEC’s register using the unique identification number (UIN), thus reducing the steps required to complete the form.

The platform automatically blocks death certification for a person whose death has already been recorded. It easily produces and provides death certificates to the deceased’s family, and it can be used by institutions to cancel payments for deceased beneficiaries. This tool is available to all medical personnel, including forensic professionals in judicial institutions.

From August 2016 to April 2017, 135 workshops were organized to train more than 2,500 doctors to use the platform to complete a death certificate. RENIEC, the Ministry of Health, and the National Institute of Statistics are working together to improve implementation of the platform in health facilities and coverage of death registration.

Digitization

During its almost 25 years of history, RENIEC has made significant progress in implementing a widely decentralized system, increasing the coverage of registration of vital events, identifying citizens, and integrating CRVS and ID management systems. It has built the civil registration database and the identification register — cornerstones of the integration — by establishing standard processes and guidelines, introducing digital technology, and digitizing civil registration and identification records.

Computerization

One of the two major databases managed by RENIEC is the Sistema Integrado de Registros Civiles y Microformas (SIRCM), or integrated civil registration and microforms system. This is the country’s main civil registration database, which combines current and historical records within a single digital repository. Documents can be retrieved at any RENIEC or decentralized office once they are integrated into SIRCM.

SIRCM serves two purposes:

- It functions as an online platform where civil registrars (in both RENIEC offices and connected municipal offices) can register vital events; and

- It works as a digital database that combines text and images of physical documents and civil registration records (that are certified microforms of original documentation).

Vital events can be registered manually or online. Information is entered electronically in RENIEC offices and decentralized offices that are connected to SIRCM, but some decentralized offices use paper-based strategies due to connectivity issues.

Processing and linking information for vital events that are registered online is relatively straightforward. When information is entered directly into the civil register, it is automatically linked with the identification register through the UIN. For example, using a mother’s UIN on a birth registration form generates information on her complete name and address. Currently, most registrars sign certificates using an electronic signature. A certified copy is printed and handed to the applicant. Information recorded in the civil registration database can later be retrieved when people request a national ID card.

Physical records are historical civil registration archives and documents that are generated from manual registration procedures in the Offices of the Registries of the Civil State (OREC). Physical documents and civil registration books are delivered to RENIEC headquarters in Lima, where they are classified and digitized. This involves entering data from paper records and creating digital images that are turned into microforms (Table 4).

Online registration services at health facilities

Following an agreement signed by RENIEC and Peru’s Ministry of Health in 2012, health facilities have access to the Sistema de Registro del Certificado de Nacido Vivo en Línea (certificate of live birth online registration system), which was designed by RENIEC. This allows doctors and obstetricians who assisted the mother to register a birth and generate the certificate of live birth. There are several benefits to providing this access:

- It helps reduce the risk of false or duplicate identities;

- It securely identifies the mother and health professionals with their ID numbers; and

- It simplifies the birth registration process by making certificate of live birth information (which is required for birth registration) available through RENIEC’s civil registration database using the mother’s UIN.

Birth registrations and requests for minor ID cards, which are issued for citizens under age 18, can be completed in one of 183 civil registration offices in public and private health centres. This has increased timely registration rates, with approximately 85 percent of births currently registered online.

Mobile technology application

Mobile technology is not used for civil registration processes.

Unique identification number

A UIN is assigned with every birth registration. Since 2005, UINs are included on paper registration forms and in the civil registration online platform. They accompany individuals throughout their lives. UINs are 8-digit sequential numbers with an additional verification digit at the end. These do not reveal date of birth, location, or gender. This number becomes the national ID number and, along with biometrics, is used by RENIEC to build and link civil registration and ID databases, and to authenticate identity.

Children are covered by the Sistema Integrado de Salud, Peru’s integrated health system, as soon as they receive their UIN. Furthermore, UINs must legally be used as the only valid identification number in

- tax and military registers;

- driver’s licences;

- passports;

- social security credentials; and

- all institutions and procedures where a register must be adopted.

RENIEC, in collaboration with Peru’s Ministry of Health, is exploring the possibility of adding UINs to certificates of live birth to initiate the identification process immediately at birth.

Integrated databases

RENIEC’s civil registration and identification registers are linked through UINs. This helps ensure that changes in civil registration are reflected in a citizen’s identity.

Changes are not automatically updated, but when a vital event is recorded in the civil register, the system generates an alert in the identification register. This notifies officials that a new civil registration record is available.

All citizens are legally required to inform RENIEC offices of any change in their personal information and request rectification. Failure to do so carries a financial penalty equal to 0.2 percent of the Unidad Impositiva Tributaria, or taxation unit (approximately US$2.60). This ensures accurate information on citizens’ identity and creates a strong ID management system based on current, reliable civil registration information.

For marriage registrations, spouses must notify RENIEC to update the identification register. If they do not, the alert will be flagged, and they will be unable to renew or replace their national ID card (in case of loss or theft) until the rectification is made.

Digitization of historical civil registration records

RENIEC is implementing a strategy to gradually integrate all decentralized offices. This includes retrieving historical civil registration records from municipalities to include them in the centralized RENIEC archives.

In 2010, an internal resolution required all Peruvian civil registration offices to send archived registration records, or duplicate records, dating back to 1997 to be incorporated into the digital civil registration database. RENIEC estimates that approximately 60 million civil registration records were maintained by municipal governments, of which around 14 million have been digitized (Table 5).

Link with identification system

All Peruvian nationals must legally have a national ID card at birth. Citizens can visit any of RENIEC’s ID offices to receive an ID card, including RENIEC offices set in health facilities in the case of newborns. Peruvians living abroad can obtain their national ID at consular offices. RENIEC issues two types of national ID cards: minor’s ID (birth to 18 years) and adult’s ID for ages 18 and over.

RENIEC is not only responsible for keeping the civil register, but also for managing and updating the Registro Único de Identificación de las Personas Naturales, or unique identification register. Citizens’ identity information is entered into this register’s database when they get their first national ID card and it remains there until their death.

A detailed overview of links between CRVS and identity management, including with other government actors, is provided in Figure 2.

Interface with other sectors and operations

From 2015 to 2018, RENIEC signed a total of 2,201 agreements with public and private institutions to grant access to the identification register. Of these,

- 1,547 provide access through the Internet;

- 404 share biometric verification;

- 159 allow access through a dedicated line; and

- 91 allow web access.

During that period, the number of queries to the identification register grew by an average of 49 percent. Some services are provided for a fee, particularly those used by private companies. In addition, RENIEC regularly shares lists of deceased citizens, including ID number and date of death, with public institutions responsible for implementing social programs to update their functional registers.

EsSalud (Seguro Social de Salud) is the public health insurance agency that provides health coverage for 11 million workers in Peru. In 2018, EsSalud signed an agreement with RENIEC to access the institution’s database of live birth certificates registered in health facilities using the online platform. This allows EsSalud to check the database daily, retrieve mothers’ identification information, and immediately complete the eligibility evaluation. If the evaluation is positive, the system sends a payment authorization to the National Bank (public banking institution with a nationwide network of offices) so that beneficiaries can collect their money.

According to the Constitution (Article 177), RENIEC is part of Peru’s electoral system, together with the Jurado Nacional de Elecciones (national jury of elections) and the Oficina Nacional de Procesos Electorales, or the national office for electoral processes. As such, one of RENIEC’s constitutional mandates is to help maintain an updated electoral register. RENIEC sends updates on the electoral roll to the national office for electoral processes every three months.

Sample registration forms

Improvement initiatives and external support

Improvement plan and budget

Strategic plan

A five-year costed strategic plan, called the Peru National Plan Against the Lack of Documentation (Plan Nacional Peru Contra la Indocumentación) 2017–2021, has been designed by RENIEC in consultation with 28 public and private entities. This strategic document elaborates policies aimed at reaching out and registering the remaining 0.7 percent of the population without a birth certificate or national identification document.

Budgetary allocations and requirements

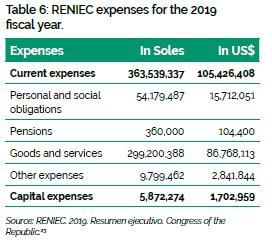

Government treasury allocation for RENIEC for the 2019 fiscal year was projected at US$212 million (Table 6).

(Table 6)

Activities identified as high priorities

RENIEC was identified as a priority and extrabudgetary activity in 2019. It focuses on closing the gap of undocumented citizens and maintaining identification processes in rural and urban areas that target marginalized communities.

Support from development partners

The development partners that provided support to the civil registration and vital statistics systems improvement initiative are listed in Table 7.

Additional Materials

Websites

Additional materials

Calderón, E. 2019. Registros civiles y oficinas de identificación. Análisis y fichas de país. Inter-American Development Bank. publications.iadb. org/publications/spanish/document/Registros_civiles_y_oficinas_de_identificación_análisis_y_fichas_de_país_es.pdf

Centre of Excellence for Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) Systems. 2019. Compendium of Good Practices in Linking Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) and Identity Management Systems. Peru case study. International Development Research Centre, Ottawa, ON. crvssystems.ca/sites/default/files/assets/files/CRVS_Peru_e_WEB.pdf

MINSA (Ministry of Health). 2018. Análisis de Situación de Salud del Peru. Centro Nacional de Epidemiología, Prevención y Control de Enfermedades. dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/asis/Asis_peru19.pdf

MINSA (Ministry of Health). 2017. Sistema Nacional de Defunciones en Línea en el Perú: SINADEF. Poster presented at the VIII RELACSIS meeting, May 2017, Nicaragua. paho.org/relacsis/index.php/es/docs/recursos/reuniones-relacsis/8vareunion/posters-viii-reunion/54-viii-relacsisposter-45/file

RENIEC. 2018. Resumen Ejecutivo del Proyecto de Presupuesto Para el año Fiscal. congreso.gob.pe/Docs/comisiones2018/Presupuesto/files/resumen_ejecutivo_presupuesto_2018_(10set2018).pdf

Conclusion

Peru has made remarkable progress in the last two decades, with RENIEC reaching almost universal coverage of birth registration and identification. However, there are still segments of the population that are traditionally left on the margins, especially in communities where vulnerabilities overlap, such as geographic isolation, Indigenous minorities, and poverty. To close the gap, RENIEC has systematically built alliances with other public agencies to expand its reach across the country and increase awareness of the importance of civil registration and identification among the population. RENIEC has become Peru’s most trusted institution as a result. RENIEC’s ability to provide reliable data, combined with its contribution to service provision efficiency and inclusivity, illustrates how integrating CRVS and identity management systems is fundamental to guaranteeing citizens’ access to rights and implementing better policies.

Endnotes

[footnotes]